A TASTE OF SAINT LUCIA!

By Osayi Endolyn

St. Lucia’s shimmering beaches and lush mountain peaks are known as some of the most beautiful in the Caribbean. But the island’s food and farming traditions have remained mostly out of the spotlight.

The drive from Jade Mountain resort to its Emerald Estate Farm takes only 20 minutes, but 20 minutes passes differently on the island of St. Lucia. Fuchsia bougainvillea and leafy palms dance in the wind along curvy, bumpy roads that require even the most impatient driver to slow down. Fruit trees proffer their low-hanging goods in the yards of pastel-colored houses, where clotheslines billow with laundry in the breeze. Hummingbirds are everywhere. The few pedestrians out in the midday heat are focused but not hurried, sometimes giving a nod or wave to my driver as they navigate a shared narrow road. To be in St. Lucia is to defer to nature. It’s not that time doesn’t matter. Time just isn’t in charge.

Deferring to nature means that when the weather is clear, you dry freshly harvested cocoa beans in the sun; when it’s about to rain, the wooden trays lined with the fermenting beans are moved into sheds before they are made into chocolate. When mangoes are in season, you eat them plain, or turn them into chutneys, jams, and juices. When the vanilla-bean flower opens for a few days, you quickly pollinate the plant by hand to ensure a small batch of pods emerge. In St. Lucia, great Mother Nature is still the boss of when and what to eat. In resort restaurants that welcome primarily tourists from the U.S. and U.K., menu offerings have become more localized, more Creole, in recent years. And how fortunate for me, because, as we pull up to the farm, it’s nearly time for lunch.

I am willing to bet that if you do not claim Caribbean heritage, even if you have regularly visited this diverse region, you cannot distinguish between the cuisines of the islands. You may have had exquisite snapper, yellowfin tuna, or mahi-mahi. Perhaps you enjoyed fresh tamarind or young coconut, scooping the white flesh into your mouth after drinking the water straight from its husk. Myriad cultures across the region resolutely center food in all manner of rituals and social pastimes. But outsiders tend to speak vaguely—if at all—about what is meant by “Creole cooking.”

A visit to Mexico City requires a tour of tacos de guisado, just as Provence in the summertime is a postcard for the latest rosé. Crawfish season in New Orleans means the calendar is full of festive crawfish boils with friends. In Amman, coffee comes dressed up with warming, aromatic spices; you could order an Americano, but why would you?

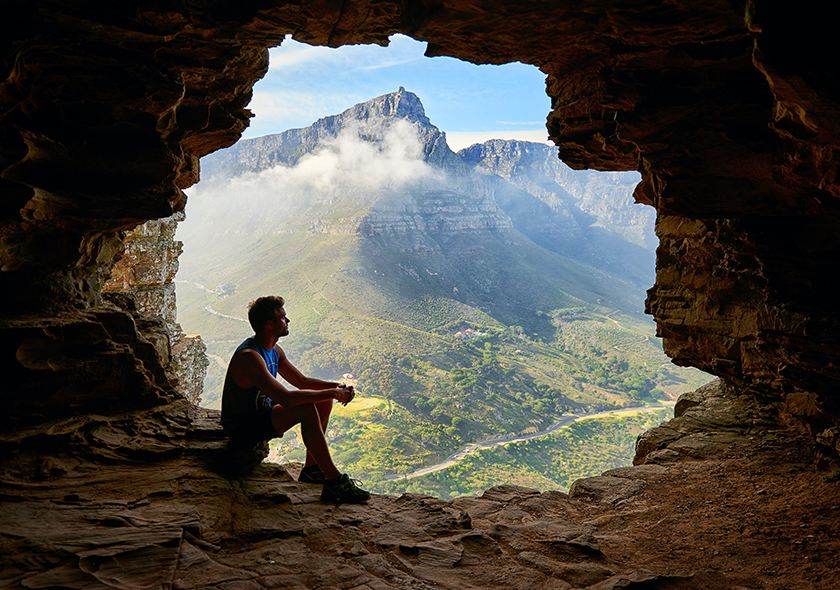

Similarly, visitors to St. Lucia aren’t just coming for the stunning views of the Gros and Petit Pitons, or to play watersports along pristine protected beaches anymore. As St. Lucian hotels and restaurants leverage their own land and work with farmers to facilitate a more independent system, their intent is to celebrate the island’s cuisine and Afrocentric heritage. Take Emerald Estate Farm, which has been cultivating organic foods for use at the restaurants of Jade Mountain and its sister resort, Anse Chastanet, since 2007. And so in your next vacation recap, you might not focus on the way the shoreline shimmers at sunset, but instead pay homage to roasted fish in citrusy souskaye, piping-hot accra fritters, or green fig (unripe banana) and saltfish with bakes (an airy fried dough) and cocoa tea.

Views are indeed shifting. More chefs from a wider range of backgrounds are being acknowledged for their contributions, more docuseries and podcasts celebrate a wider range of food traditions. Incrementally, fewer Global South cultures find their foods consigned to “cheap eats” lists (as if every expression of French cuisine were haute). At the same time, St. Lucians I spoke with during my visit described an ongoing cultural transition that has deepened their own appreciation of the island’s rich history, both in the kitchen and beyond.

CENTURIES-OLD SOCIETIES built by the Arawak and Carib Indians were in place before St. Lucia was added to the colonial map in 1651. The drastic influx of Africans from the trafficking of enslaved people shifted the island makeup yet again, as did the indentured East Indian laborers who were brought to replace them following abolition in 1834. As a cultural presence, St. Lucia is ancient. As a nation telling its own story, it’s relatively new—the island didn’t secure its full independence from the U.K. until 1979.

Part of the effort to shape a national identity is to prioritize what really matters. One of the challenges for tourist properties here is aligning food supply with guest demand. (With visitors outnumbering the population by nearly two to one in recent years, food imports are a must.) The country spends millions of dollars annually on food imports, with hotel brands in particular concerned with meeting tourist expectations. A more streamlined ordering system and better communication between hoteliers, chefs, and farmers could help to reduce that cost, while better supporting the local economy and addressing issues like systemic poverty and food insecurity.

When native chefs with Creole training get to cook for guests eager to experience a menu that reflects the island, the entire story of what it means to visit St. Lucia changes. You’re not only snorkeling at the base of the majestic Pitons or slathering yourself with geothermal mud in the iconic Sulphur Springs. What you remember is the juice of sweet soursop drizzling down your chin as you gnaw around the seeds to tease out the pale flesh. You note the aromatic herbs that accent the line-caught ahi tuna tartare at Balawoo, the fine-dining restaurant at Anse Chastanet. A hash made from “ground provisions” (root vegetables) makes an appearance with grilled fish, brightened in pineapple souskaye.

You would talk about the slow rolling burn of spiced heat in a goat vindaloo that awakens every facial nerve, such as the one I had at Aspara, the resort’s East Indian Caribbean restaurant. Gazing westward at sunset, lilac-rose hues brighten the sky. But what amazes you is the perseverance of uncredited cooks who created these dishes over hot-coal pots, in front of clay ovens, whose skills and techniques are kept alive in these recipes.

“To me, this philosophical shift happened pretty recently,” says Damian Adjodha, who manages Emerald Estate. En route to our meal, he walks me through what is more jungle than typical farm. “We are trying to farm in a way the people around here would farm,” he says, referring to the trees, shrubs, and other naturally occurring plants that coexist with the cultivated ones. We pass a felled breadfruit tree that spawned descendants now producing their own fruit. Beloved as the potato of the Caribbean, breadfruit is a resilient crop, nutrient-rich and versatile, and integral to the island diet. “Breadfruit is part of our culture so deeply that when people buy or build a house the first thing they want to do is plant a breadfruit tree and a mango tree. That’s food security,” Adjodha says.

As we walk, he points out a group of cocoa trees, and later, when I visit Jade Mountain’s Chocolate Lab, I realize the bars melting in my mouth were made from cocoa harvested from this land. And waiting for us in a covered sitting area with a mosaic-like mise en place is Frank Faucher, the resort’s chef de cuisine.

For our lunch, Faucher prepares a salad to start: tomatoes, orange, cucumber, guava skin, red onion, watercress leaf, and a compressed pineapple he has marinated in warming spices. For the main event, Faucher is making a one pot, a stewed dish that is just what it sounds like. To a heated saucepan he adds onion, garlic, yam, breadfruit, dasheen (taro root), and green fig. He stirs and stirs, then adds fresh bay leaves, cinnamon bark, a heaping spoonful of curry powder, coconut milk, culantro (similar to, but stronger in flavor than its cousin, cilantro), celery herb, and seasoning peppers. He brings the pot to a simmer, then looks up and smiles, spooning a hefty serving into my bowl. “This is Creole cooking,” he says.

Faucher’s style is influenced by Ital, the vegetarian cuisine developed in Rastafarian culture that can be found throughout the Caribbean today. His St. Lucian grandparents would have made a leafy callaloo using breadfruit as the body of the dish rather than trotters, cow feet, or saltfish, he says, describing an Afro-Caribbean tradition of plant-based cuisine that was common here well before it was in fashion or labeled vegan. “We have a long history,” Faucher says. “These are the old ways.” Indeed: it’s a sunny and humid 80 degrees and I’m throwing down a steamy, hot stew while looking out at dense, verdant looping hills. This was food cultivated with medicinal knowledge, intended, during at least one era of history, to restore and strengthen overworked and unappreciated bodies. It all makes perfect sense.

Awareness of and appreciation for Creole cooking in St. Lucia isn’t only about savory dishes. It’s also about raw ingredients. Visitors may be surprised to learn how integral cacao is to St. Lucian food-and-beverage culture. The trees are found on farms, in residential yards, and on estates.

Peter Gabriel, chocolatier at the Jade Mountain Chocolate Lab and a staff member at the resort for eight years, is responsible for Emerald Estate’s divine chocolate bars. “Chocolate takes a lot of time and a lot of patience,” he says during a demonstration. His work space is efficient—he can walk the length of it in only a few strides. He guides his small audience through melting, tempering, and setting bars of chocolate. The cacao tree bears large pods that, when cracked open, reveal damp clusters of beans that are encased in a white pulp. Colloquially called “jungle M&M’s,” Gabriel encouraged me to try one. “Just don’t bite into it,” he warned, cautioning me to enjoy the sweet pulp but spit out the bitter seed.

Jade Mountain—which was designed by its architect owner, Nick Troubetzkoy, and opened in 2006—has more than 2,000 cacao trees growing throughout the property, which includes Anse Chastanet, and at Emerald Estate. It takes two cacao pods to make a single bar of chocolate, and one tree yields around 25 pods per year. My demo companions and I have skipped over the arduous parts: harvesting the pods, cracking them open with machetes, extracting the pulpy beans, then fermenting them outdoors in wooden trays for one week.

We’re standing in one of the resort’s only air-conditioned spaces learning how to temper dried nibs into a shiny, smooth paste on a marble counter. We each set our chocolate in bar trays and add accoutrements, like dried fruit, nuts, and spices. I choose pineapple and salt. The conversation shifts to chocolate’s origins. I watch a man from Atlanta raise his eyebrows in genuine surprise as Gabriel mentions Ghana as a top producer of raw cacao. The man asks him to repeat that. Gabriel nods as he wipes down the counter. “Yes,” he repeats in his St. Lucian lilt. “Your chocolate is West African.”

Chocolate was born in the Olmec, Mayan, and Aztec cultures in Central and South America and proliferated as part of an epic colonial global trade. Today the majority of chocolate comes from Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. It’s revealing that chocolatiers in the U.S. and Europe often fail to describe the Latin and African origins of the chocolate they source.

Most St. Lucian chocolate is sold only on the island, a result of small-batch growth and processing, and also reflective of an ongoing colonial pyramid: countries that produce raw material such as cacao struggle against major manufacturers to set fairer prices for growers and often end up being forced to re-import finished products at steep rates.

I consider all this the next morning over my handheld breakfast of cocoa tea and bakes at the outdoor Soufrière market. The cocoa tea, which is brewed from a freshly grated stick of 100 percent cacao, is mixed with spices like fresh nutmeg, cinnamon, or ginger; the result is as varied as the number of ways you take your tea or coffee. Add sugar, add milk if you like. Sipped while eating bakes, life gets better.

I watched a woman fry those bakes in a cast-iron pot over a coal fire at the edge of the market. People gathered around, greeting each other, setting down bags of just-bought cherries, mangoes, and tamarind pods. They made small talk in patois and got into each other’s business, ignoring the pleas of a preacher at the market entrance yelling over a microphone about God’s Plans. A chicken poked around, unbothered by everyone. I heard an American woman ask around if anyone had coffee. It pained me to see the effort made by the folks at the market, who seemed to expect the question before it was asked. No, sorry. No coffee today.

I wanted to say to her, “You’re in St. Lucia. You’re surrounded by resplendent cocoa trees. You’re talking to folks who packed up their freshly brewed, piping hot, expertly seasoned cocoa tea to sell to you. They’ve been here for you, since before sunrise. Maybe skip the drip. Be a local this trip. What could it cost you? What could you gain?”

A TASTE OF ST. LUCIA

WHERE TO STAY

Anse Chastanet

Like its sister resort, Jade Mountain, rooms here are partially open-air and designed to take advantage of cool breezes—giving them the feel of sleeping in a very luxurious tree house. In addition to adventure sports and guided nature walks, the property is increasing its wellness offerings, which include private holistic health classes, as well as a vegan restaurant, Emeralds, which uses organic produce from the nearby Emerald Estate Farm. ansechastanet.com; doubles from $450.

Jade Mountain

Part of a 600-acre estate shared with Anse Chastanet, this hilltop resort offers stunning views and easy access to two of the best beaches on the island—Chastanet and Mamin. Suites here eschew a fourth wall to reveal uninhibited vistas of the Pitons, at which you can marvel from your private infinity pool. jademountain.com; doubles from $1,285.

Ladera Resort

High above the Caribbean Sea, Ladera is a former cocoa plantation that now houses verdant tropical gardens, with buildings made of local stone and hardwood. Chef Nigel Mitchel and his team have created a unique St. Lucian-meets-French fine-dining experience at the resort’s restaurant, Dasheene, which uses a bounty of locally grown ingredients. ladera.com; doubles from $875.

WHAT TO DO

Emerald Estate Farm

A 20-minute drive from Jade Mountain through the hills of Soufrière, you’ll find the resort’s 40-acre organic farm, which supplies produce for both Jade Mountain and Anse Chastanet. Guests of the resorts can tour the property—which grows everything from microgreens to nuts and herbs (plus more than 1,000 cocoa trees)—with farm manager Damian Adjodha. jademountain.com.

Project Chocolat

The cocoa farm at the 250-year-old Rabot Estate features a “tree to bar” tour with hands-on demonstrations. It’s a delightful experience, thanks to a fascinating walk in lush rain forest, where visitors can see cocoa in its most natural form. (Guests leave with a chocolate bar they’ve made themselves.) And the excellent restaurant incorporates cocoa seeds into almost everything, from cacao-nib-rubbed mahimahi to salad dressings infused with citrus and cacao. hotelchocolat.com; tours from $61.

Soufrière Market

While there is generally some kind of farmers’ market every day of the week in Soufrière, the “big” event takes place on Saturday mornings around downtown’s Fisheries Complex. All manner of tropical fruits, vegetables, and St. Lucian specialties (like saltfish, bakes, and cocoa tea) are sold by local vendors.

Recent Posts

Celebrate Valentine’s in Saint Lucia

2026 New Year’s Message by SLHTA President Erwin Louisy

Tags